A few weeks back, we had a look at one of my elite athletes, Aoife Cooke. Aoife’s grafting away to gain a place on the Irish team for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics (marathon) and the 2020 World Half Marathon Championships. Again, I was inundated with emails about various aspects of her training and there were a good few posts on Facebook about her workouts and progress.

The topics ranged from the hill sessions Aoife bangs-out (10-20×15”) to her mileage increase, strength and conditioning, high density/big volume workouts, and her endurance spine.

Over the next few weeks, I’m going to explain more about the endurance spine, and how and why you should incorporate it into your year-round training. I’ll explain why the old tempo methods of lactate threshold/anaerobic threshold and

Most runners go out on a Saturday or Sunday and drop out a long run. The majority of these plod around in the belief that time on their feet is great training.

In marathon specific build-ups, most incorporate some sort of marathon pace work into their weekend long run.

I suspect, most of you reading this combine the two methods: you go out on the weekend with your friends/club and run for a couple of hours, chatting away about how the world will end. Then, twelve-sixteen weeks before your spring or autumn/fall marathon, you start your marathon training and slip in some marathon pace work.

The first mistake most people make with the marathon is that they run two+ marathons a year. (Note: I’m talking about people trying to make decent improvements.) You/they see elites doing this, so you/they think it’s the right move. Wrong.

Elites race for money—it’s a job. Most have time to rest and recover everyday. Generally, they have physical therapists they go to for massages and sorting niggles out—daily/weekly. The more successful elites, definitely have time to rest and recover between runs. You have a family, work, and other commitments—time is a precious commodity.

If you run two marathons a year, you’re giving yourself six months before a marathon. You spend the month after a marathon recovering, getting back into the swing of things, and boring work colleagues with fishermanesque tales of your endeavours.

This leaves you with five months. Let’s say your marathon specific build-up is twelve weeks/three months, including whatever taper you take. Effectively, this means you have two months or so before starting your marathon build-up.

The first month of your two months prior to you marathon build-up is probably spent getting back into some sort of training rhythm. You throw in some low density, high intensity speed work (not a good idea: you’re heading for an injury), you drop out a race or two. But things aren’t gelling. Same thing happens in the month before your marathon build-up. You’re not overly concerned though as you know the marathon build-up is waiting and you’ll sort things then. It’s at this point that motivation is high: you know you’re going into marathon training etc and you say, ‘yeah, it’ll be ok, the marathon’s coming soon and I’ll get fit then.’

Most likely, you grab a marathon schedule off the internet (not specifically designed for you or anybody really), grab a cut-and-paste schedule off a lazy coach, or plan out the whole 12-16 weeks with what you believe are great sessions. Invariably, you start out with verve, zest, and zeal. (Note: you should never accept a marathon schedule off a coach: a coach should dish-out your training to you weekly and, if necessary, even the weekly schedule should be tweaked on a daily basis—see below.)

Your marathon training probably sees an increase in weekly mileage, a speed session and/or a tempo, and a long run on the weekend—with some marathon pace work (every few weeks or so—again, not the best way to train for a marathon but we’ll look at his later).

A few weeks into your marathon plan…kaboom. You’re halfway through a workout and you’re not hitting the times. You trudge on through the session, get home, get in the shower, and start crying. You wonder how you can salvage your marathon training—it’s even worse if you’ve popped it up on some social media platform and everybody’s waiting for you to drop out 7x3km @ 10”-15” faster than MP off 1km @ 30” slower than mp etc—time to take a break from that platform and come back in a few months.

You get out of the shower and start editing/rubbing out sessions and changing things. You end up cramming-in half-baked workouts and so on. (You’re in panic mode.)

Halfway though your training cycle, you probably pick-up a niggle (piriformis syndrome, medial tibial stress syndrome, peroneal issues, achilles aggravation, and so on). You also start to feel fatigued. You soldier on. Your nutrition is out the window because you’re depressed that your plan isn’t working. You might make it to three weeks before marathon day, and then you start to taper (this is the wrong thing to do: your taper should only be ten days—I’ll cover this another time), and then you pick up a cold. You don’t understand why—nearly every time, during

So how should you do it? How does the endurance spine fit in and work? What is the endurance spine?

Everything depends on the individual runner.

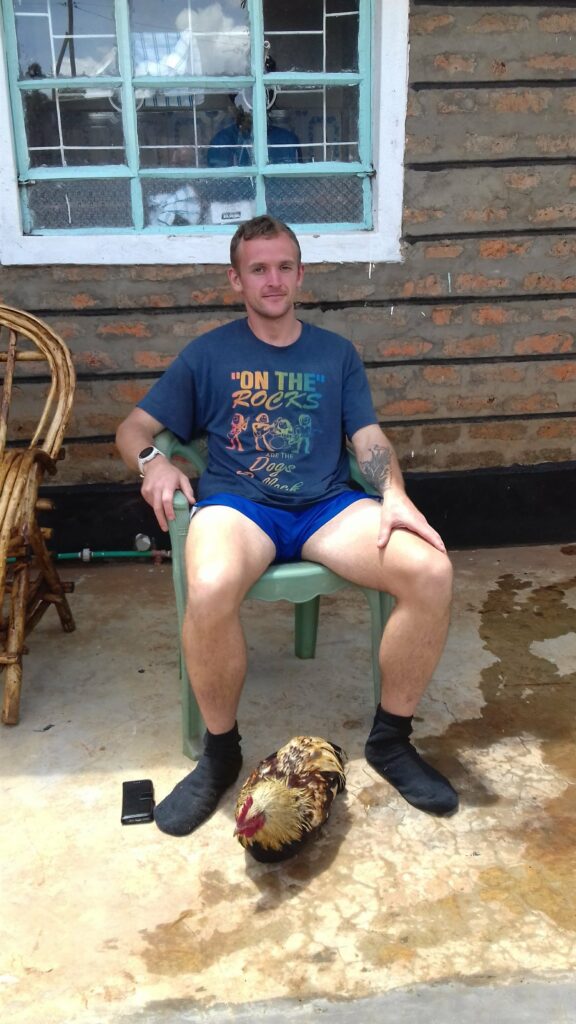

The best way to explain this is to look at a real person. But rather than pick one of my elites, we’ll select one of my runners who has only been running two years. Let’s take a look at Matthew The Chicken Slayer Maynard.

The Chicken Slayer approached me eighteen months ago. When a person contacts me about training, they complete a twelve page Profile Questionnaire that covers everything from personal details, medical history, nutrition, sporting background and so on. Here are two key points from Matthew’s PQ:

Please list all PR’s/PB’s:

1k -3:52; 1 mile – 6:25; 5k -21:03; 10k – 45:52 –Half-Marathon – 1:42:12

Rough outline of training history (weekly mileage/number of days per week/number of runs per week):40 miles now , and 16 to 20 miles a week when I started running a year ago

So, Matthew had only been running one year.

Fast forward six months and here’s Matthew’s new Half Marathon PR (Manchester 14th October): 1hr23’07” (that’s, roughly, a 19 minute improvement in six months). Two months later, in the Ribble Valley 10k—undulating course—he ran 37’35” (8 minutes + PR).

Some context…

Matthew works long, hard hours in an abattoir. Often, the cows kick and head-butt him. But, like me, he’s a hard-man. He gets up at 4am to train, then heads off to work.

.

When he first started with me, I banged him on a Stazza Super Base for twelve months.

What is a Stazza Super Base? How does the endurance spine fit in with a Stazza Super Base? How does this relate to the marathon? Stay tuned and next week I will reveal all…